Growing Up Queer

Adolescence can be a lonely time. Thankfully, we were able to see, hear, and feel ourselves through the media that made us.

“High School.”

Those two words are enough to send a shiver down any gay person’s spine. The repression! The fear! The lack of control over where we can go, what we can say, and how we can look. Is there anything more un-queer than a haircut code? Whether or not we were out of the closet at the time, the imposed social and moral codes that came with religious education, heteronormativity, and familial pressures (one, or all may apply) can take its toll on a young queer person trying to find their place in the world.

Most of us refer to this era as the Dark Ages. Some of us don’t refer to this era at all — and I don’t blame anyone for making that decision. We all coped with the difficulty, isolation, and angst of our adolescence in different ways. For some, blending in was a path to survival. “At school, people would bully me a lot and I’d try to deny that I was queer,” shares Edgy (she/her), a 26-year-old creative director, DJ, and resident of rave collective Club Euphoria. “I even felt the need to prove them wrong and court girls. I’d fumble for the main reason they’d tell me: ang lambot mo kasi, gwapo ka sana pero ang clingy mo, sobrang emotional mo. That stuck with me. Instead of fighting it, I embraced it.” At some point, standing out became a new form of armor, which sometimes came at a cost. Celeste (they/she), a 25-year-old filmmaker recalls, “A number of relationships really weakened after I came out queer and eventually transitioned. I had to let those go.”

No matter how we dealt with things, it’s almost certain that pop culture played a role in our path to self-discovery. The proof is in the pudding: pop culture plays such a huge role in queer culture, no matter what stage of life we’re in. Drag Race trivia nights, lesbian book clubs, and Broadway sing-alongs – media is etched in our DNA. We can recite movie lines verbatim because in the greater scheme of things, our interests are, quite frankly, niche. And if only a small percentage of the world actually gets what we’re talking about — we hold onto these things for dear life.

“Being exposed to [several] genres of fanfiction is possibly how I was assured of my own queerness,” reads a message from Izzy (any pronouns), a 25-year-old musician. This was a familiar pipeline to many of us. “It’s quite fun going in blind and finding out mid-story that the two love interests are of the same gender or gender-swapped. Also, seeing so much gay or gender-swapped fan art of characters on Twitter and Tumblr reassured my identity as a kid.” And before we could put a name to things, we may have had an inkling. Izzy recalls a memory from when they were three years old: “I was on top of the playground jamboree pretending that I was a princess, cutting myself off mid-sentence and it just hit me. I don’t know, something just clicked in my brain that I just kept to myself but I just knew who I was, like I was being told by some omnipresent voice, “You remember that this is who you are, so be it.”

I first came to the realization that I was queer when I was 11, and only “officially” came out of the closet a long six years later. Between those years, only a handful of people knew the truth. Where else was I to turn to? Bubbline YouTube compilations. Faberry (we’re stronger than the troops) fanfiction on Archive of Our Own. The lesbian online publication, Autostraddle, was my bible, and thankfully so because it was at its peak during the mid-2010s.

I’m one of the lucky few that found a small pocket of refuge through a queer friend group in high school. I actually found multiple interconnecting ones through my first experience of the lesbian food chain: football dirtbags who were exes with church guitar players, who were classmates with theatre nerds, who were best friends with art hoes. That’s when I learned that not all of our interests would be the same, but the core experiences of queerness were what kept us together. You could have neatly placed us into Glee-esque stereotypes. Except much cooler, because we’re all queer. Something like:

- Miss Intrams: Your typical jock, but the hips don’t lie. Goes from “team captain” to “stage mom” at a moment’s notice. To research more on the role, I spoke to Bill Barrinuevo (he/him), a 35-year-old producer. Bill grew up playing sports, but was frequently teased among his straight male relatives for being “soft.” He credits his mother for nurturing a strength in him. He tells me, “Mean people will be mean. You need to find where you feel safe and move within that space. You need to be familiar with what feels safe for you. But let me go back to mean people… I’m kind of learning this about myself as well, you have to love yourself so you can send out kindness, we can’t police people online and tell them to be kind. If they don’t love themselves, no love will come out of them.”

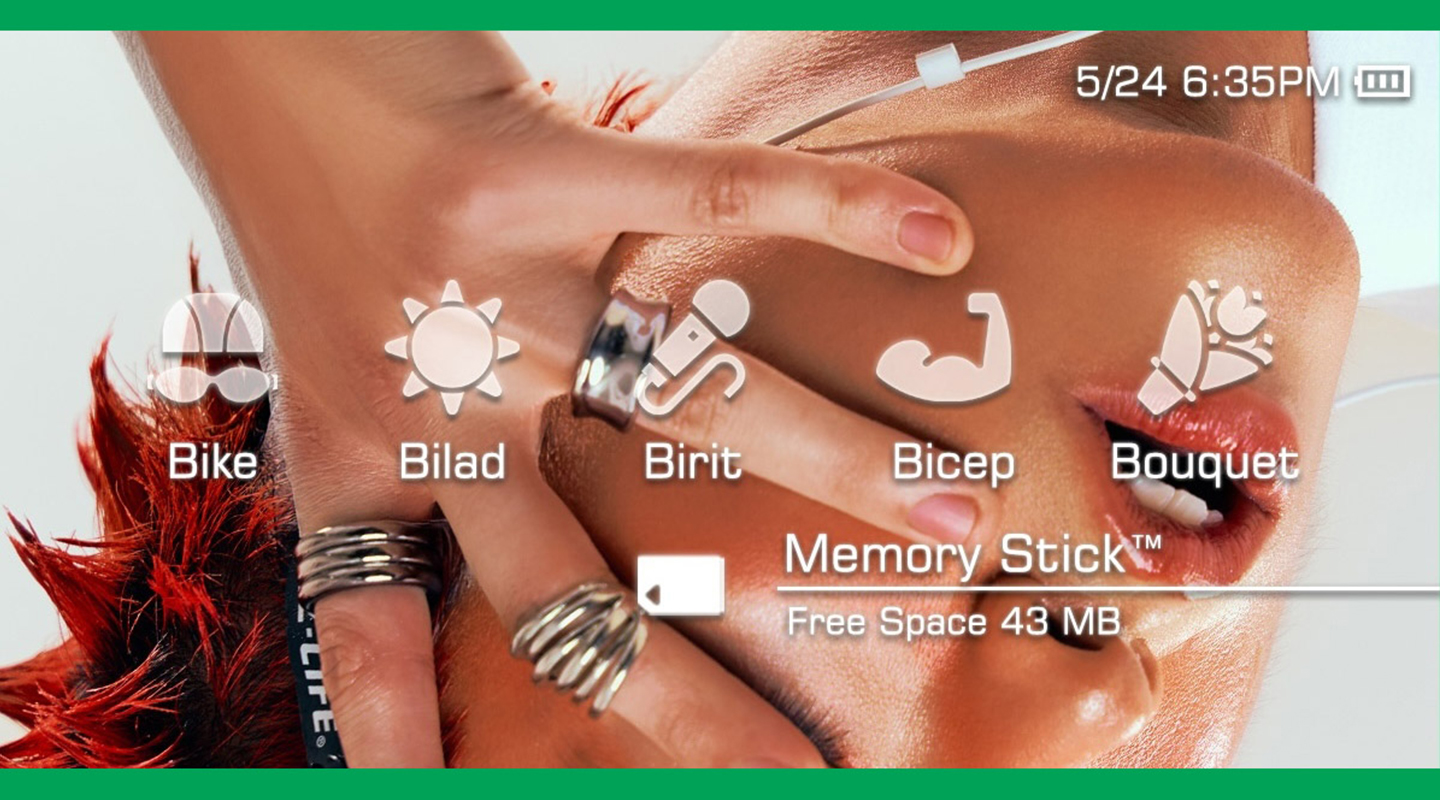

- Butch Biritero: ‘Yung classmate mong nasa likod ng classroom na laging may gitara. Ex ng bayan. Zoë (they/he), a 26-year-old actor and designer, grew up between summers of football camps, theatre workshops, and instrument lessons that led them to a love for movement and acting onstage. “I didn’t have the language to define transness and being non-binary up until college, so a lot of my childhood involved DIY-ing the media I consumed to be more ‘pasok’ to how I saw myself. I remember being such a huge fan of Captain America back then, and only later on spotting the trans allegory of his ‘creation’. Because there also wasn’t a lot of clear cut representation available, this made it easier for me to process the things I didn’t quite understand about myself yet.” “

- Look Queen: The friend na laging late sa hohol pero perfect ‘yung eyeliner. You go to them for girl problems, boy problems, and them problems — just be ready to hear the cold, hard truth. Blush (she/her), a 30-year-old marketing lead for a design company who moonlights as a budding bedroom pop star, explains that it took her some time to find her inner beauty: “I feel like I grew up in a body I was made to feel uncomfortable in. I found a lot of comfort in unusual things because I felt unusual myself. Foreign media, alternative music, and hobbies allowed me to be by myself. I like to think of this as the cocoon stage. I’m a butterfly now.”

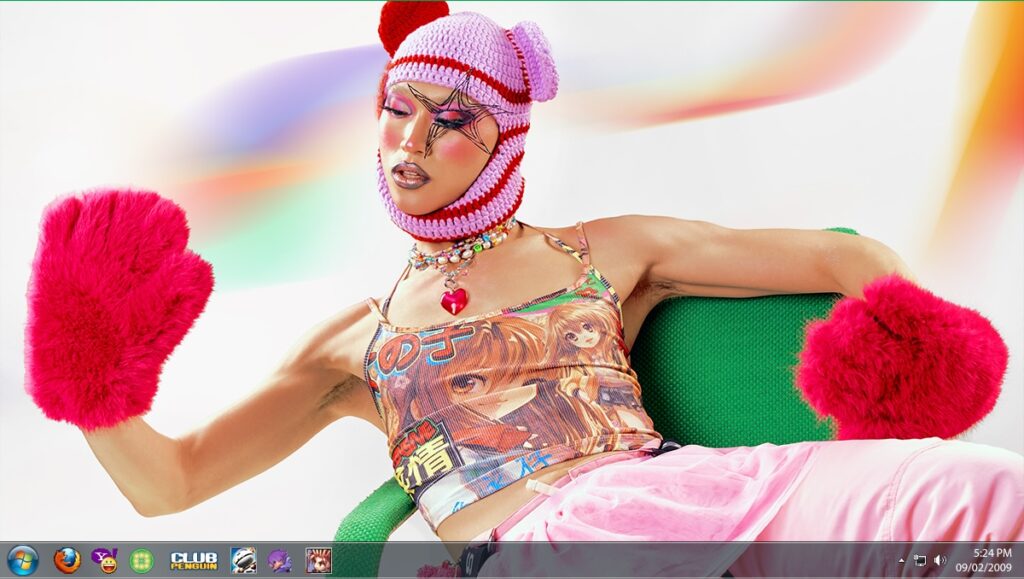

- Femme of the Future: The alternative doll who will fight all of your opps. At every gig in the city at the same time, but somehow makes time for acads. Edgy, a self-identified bruha, shares that her love for nightlife eventually evolved to a greater calling: to create safer spaces through her work with Club Euphoria. Edgy works to protect: “not just the people my age, but also to the youngsters in the queer community. To help them express themselves more and be proud of their own talents.”

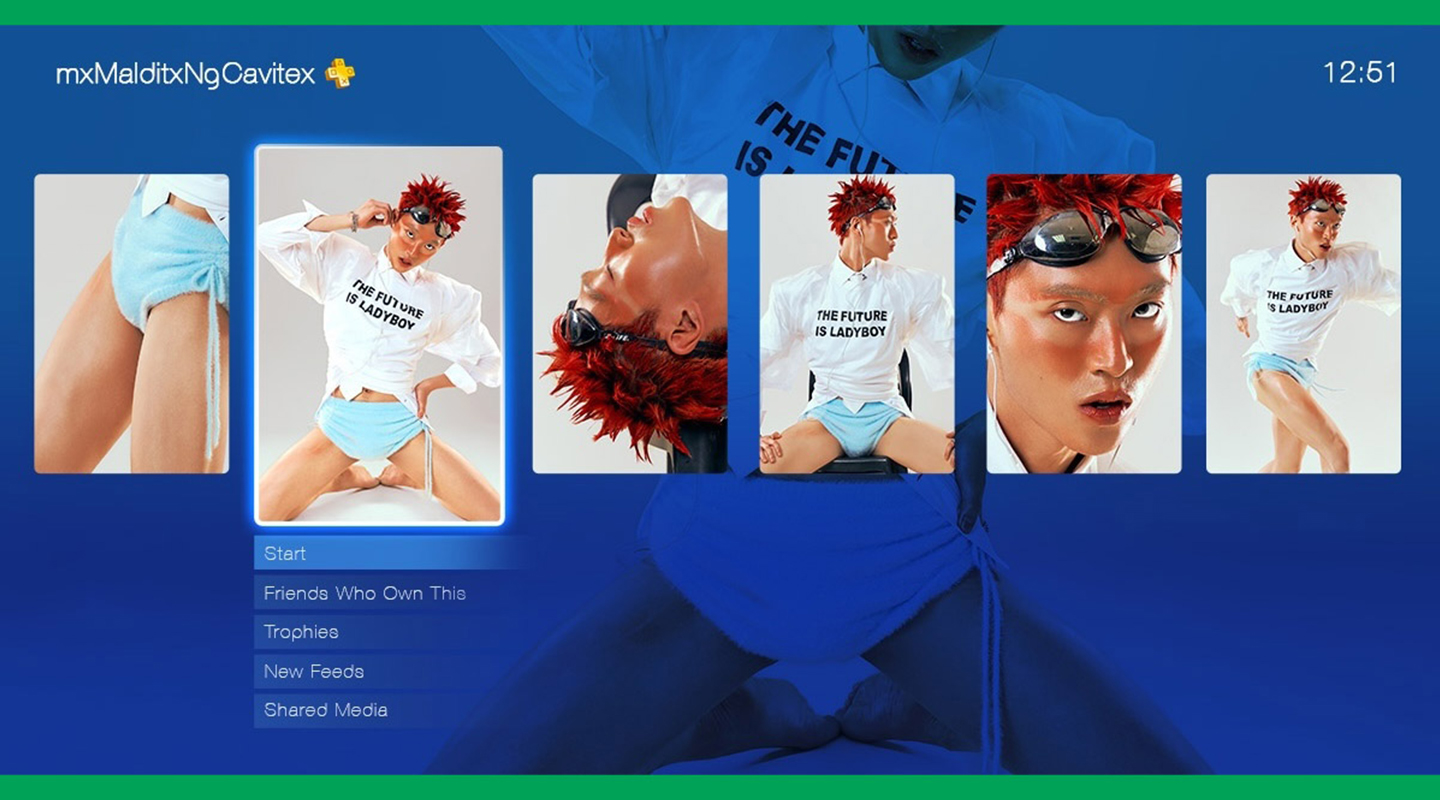

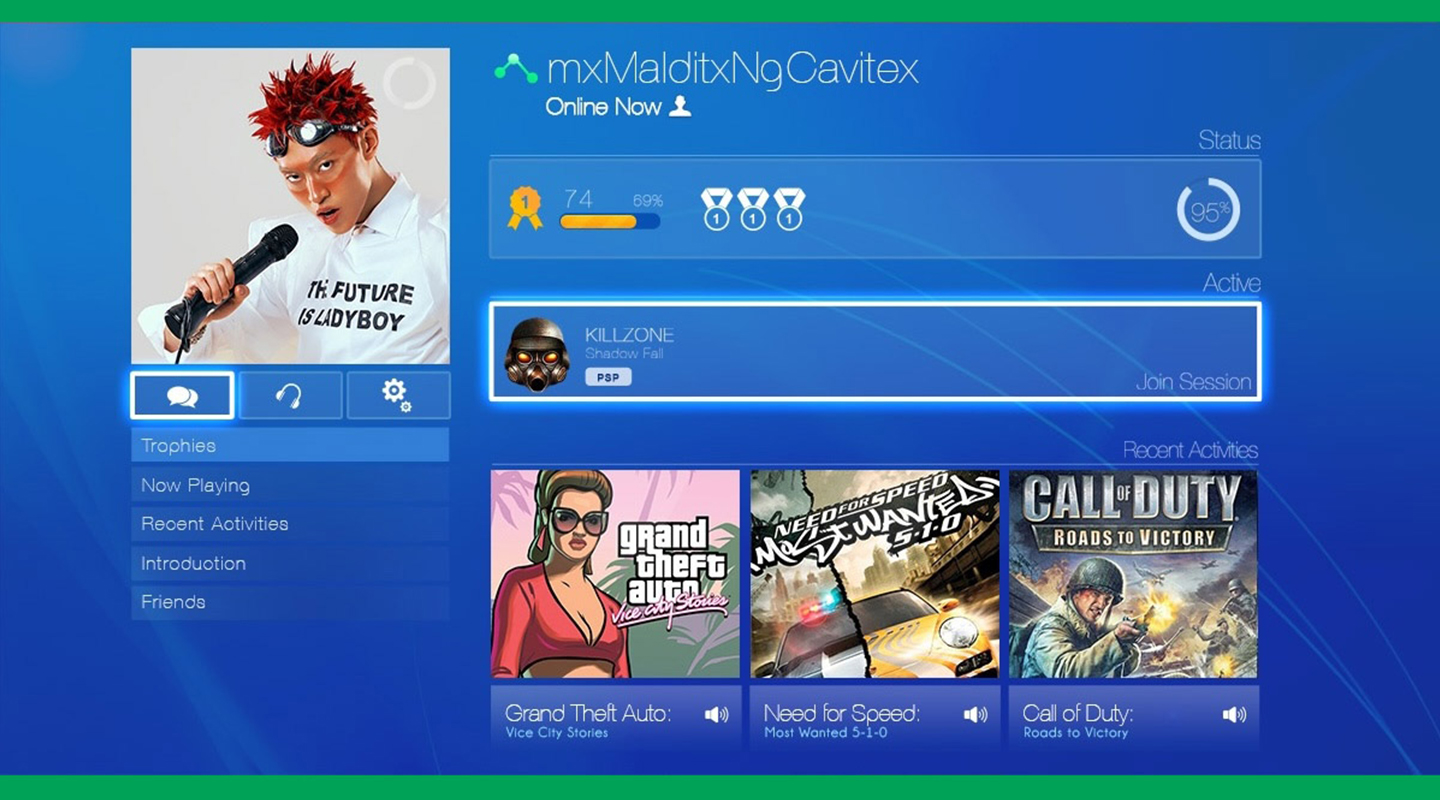

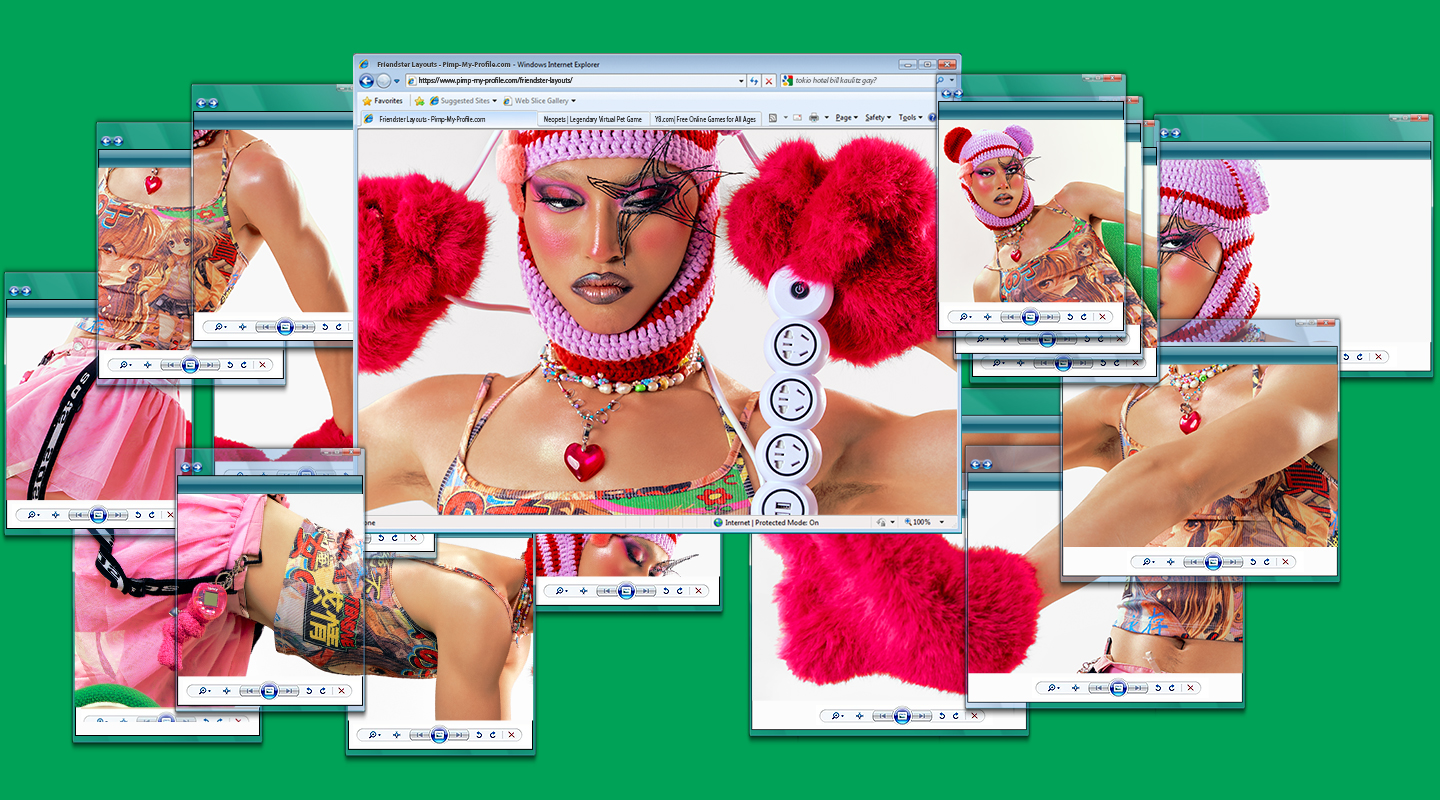

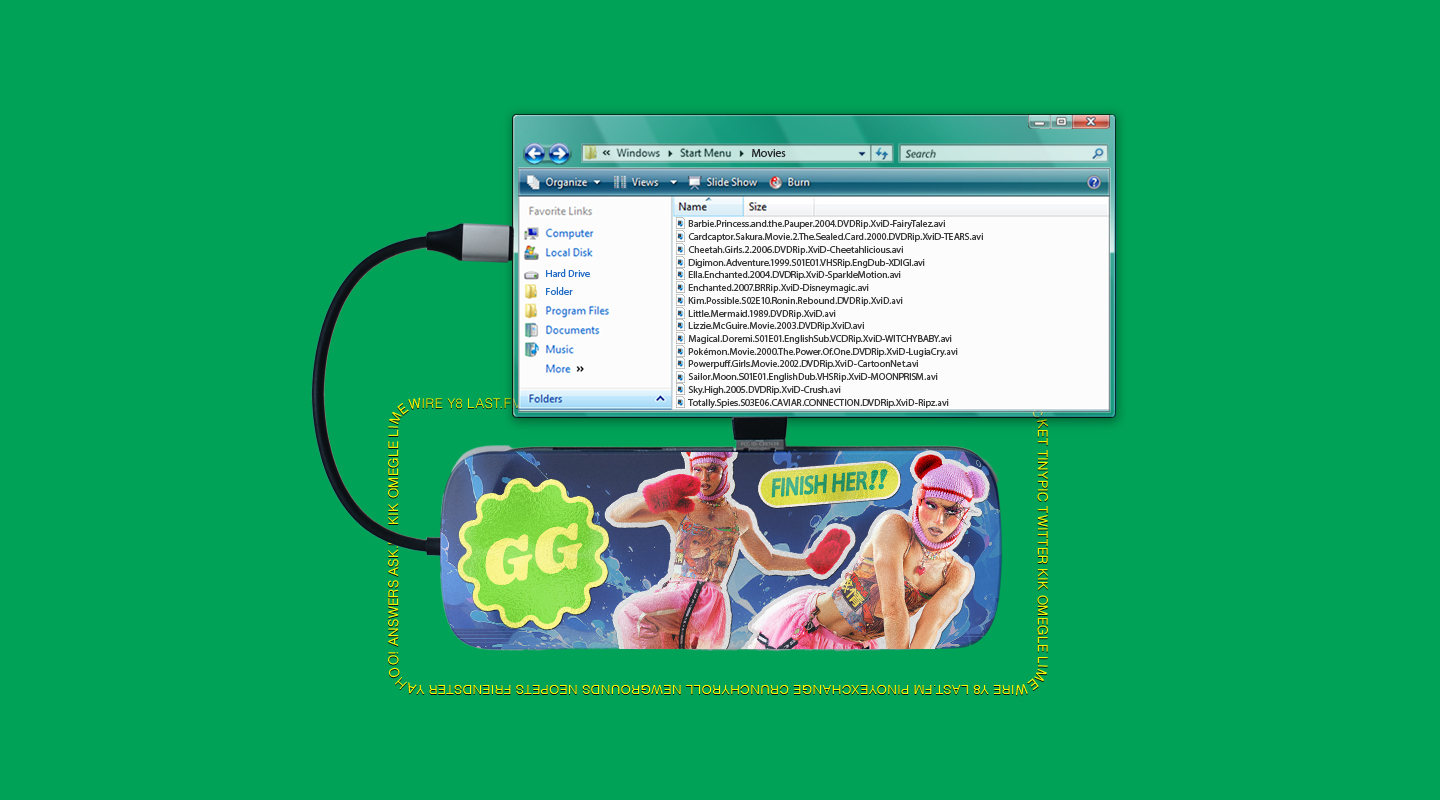

- Internet Explorer: Tahimik sa personal pero may 40k followers sa Twitter fan account. Gave you the most life-altering media recommendation that became the basis for your personality. Willar (he/him), a 35-year-old fashion designer better known by his work as Salad Day, infuses this energy into his work that explodes with internet references and true Pinoy maximalism. He tells me, “I love to follow subcultures in different platforms from fashion, to art and even gay porn.”

Every friend group had a combination of these personas. And maybe we align with more than one of these. In fact, there’s a strong chance that we do. Like Izzy, whose punk sensibilities are equally informed by their online upbringing. And Celeste, who was the token artsy kid of her batch, but also had a kinship with Filipina songstresses of that past. I personally was a Femme of the Future sun, Internet Explorer moon, Miss Intrams rising. And in my experience: these personas not only dictated what you liked, but also determined how you dealt with your queer identity being at odds with your surroundings.

When I was 11, as I was discovering my queer identity on the internet, I got really into punk and post-punk. The Ramones, Joan Jett, Joy Division, Patti Smith. I wore Doc Martens to my freshman retreat. I wore my hair in a shaggy bob to look like Quinn Fabray in Season 3 of Glee. If I weren’t too scared of what cigarettes would do to my cardio, I probably would have done that too.

I was the meme of the kid who made sure they didn’t fit in, but really, I was extremely insecure about my self-image. In order to compensate for what I felt I lacked, I became funny on Twitter. I became a class clown in real life to make up for the fact that I don’t think I ever liked how I looked in a picture until I was 15. Subculture was my savior, but it was also my armor. Later on, I’d get a taste of being popular through participating in sports, and that became my new armor. I never became vulnerable enough to even have a best friend until I met my first girlfriend, because I was so afraid of the betrayal I’d faced from a previous friendship where I was outed against my will. It took time to allow myself to be vulnerable again. A problem, as I have learned from these interviews, that isn’t uncommon in the community.

Not only did the genres of media differ between our “archetypes”, but the way that queer people consume media has evolved so quickly in the past two decades that the experience wildly differs between generations. Social media is still a relatively new invention. However, the way it was used in 2005 is wildly different from how it is used today. Before the current wave of influencing, microtrends, and TikTok, people blogged. Bloggers were the proto-influencers of the early aughts. They shared about their lives, their work, and the cool events they’d been invited to. Blogging isn’t far from what we do on social media today, but because platforms like LiveJournal catered more to long-form posts, there was a tendency to be more vulnerable and off-the-cuff. Internet culture was less centered on curation and personal branding because it was already so novel.

Bill shares that, to him, the blogosphere was another form of escapism. “In high school, I read Blogspots of college kids in arts, comm, humanities courses — so I had an idea that there is life outside of my hometown,” he shares. “It made me dream of a good college experience. It made me look forward to it.” This is yet another way queer people were able to find hope, through people who weren’t that far from where we were at the time. It’s hard to imagine how a young queer person would have had access to that perspective were it not for the Internet.

The format of cable television encouraged a monoculture where people were plugged in, watching the same global events at the same time. Now, we consume news headlines mostly through our timelines. We first experienced this through official newsroom accounts penetrating the social market through Tumblr, Twitter, and Facebook. Eventually, that would go on to shape our political views. Celeste shares, “I became a feminist at 13 because of the internet. Back when Twitter was cute.”

WIllar, who has been using the Internet since its dial-up era, points out how algorithms have changed not just the modes of consumption, but also how the experience can vary from person to person. The fast-moving pace of TikTok trend cycles points to a lack of “true monoculture” — which has allowed fringe movements to flourish. Think Flat-Earthers, 911 truthers, or plain olf TERFs. It hasn’t become uncommon to come across misogynistic, pro-genocide, or transphobic rhetoric on TikTok or Twitter. Opinions that come from communities that, like us, found each other online.

“The biggest media shift I’ve noticed in recent years is the shift towards right-wing conservatism that the world used to be able to resist. The news is filled with racism, genocide, and queerphobia that can so quickly dishearten queer youths who are still trying to find their place in the world,” says Zoë. And sometimes, the call comes from inside the house. The sheer scale of the online queer community has led to infighting and bullying among our kin. Once a certain sector of the queer community reaches a level of predominance, they can replicate the behaviors of the oppressor. “Abolish Grindr. Eme.” jokes Celeste, referring to the culture within online cruising that normalizes body-shaming, and puts a premium on able-bodied and masculine bodies.

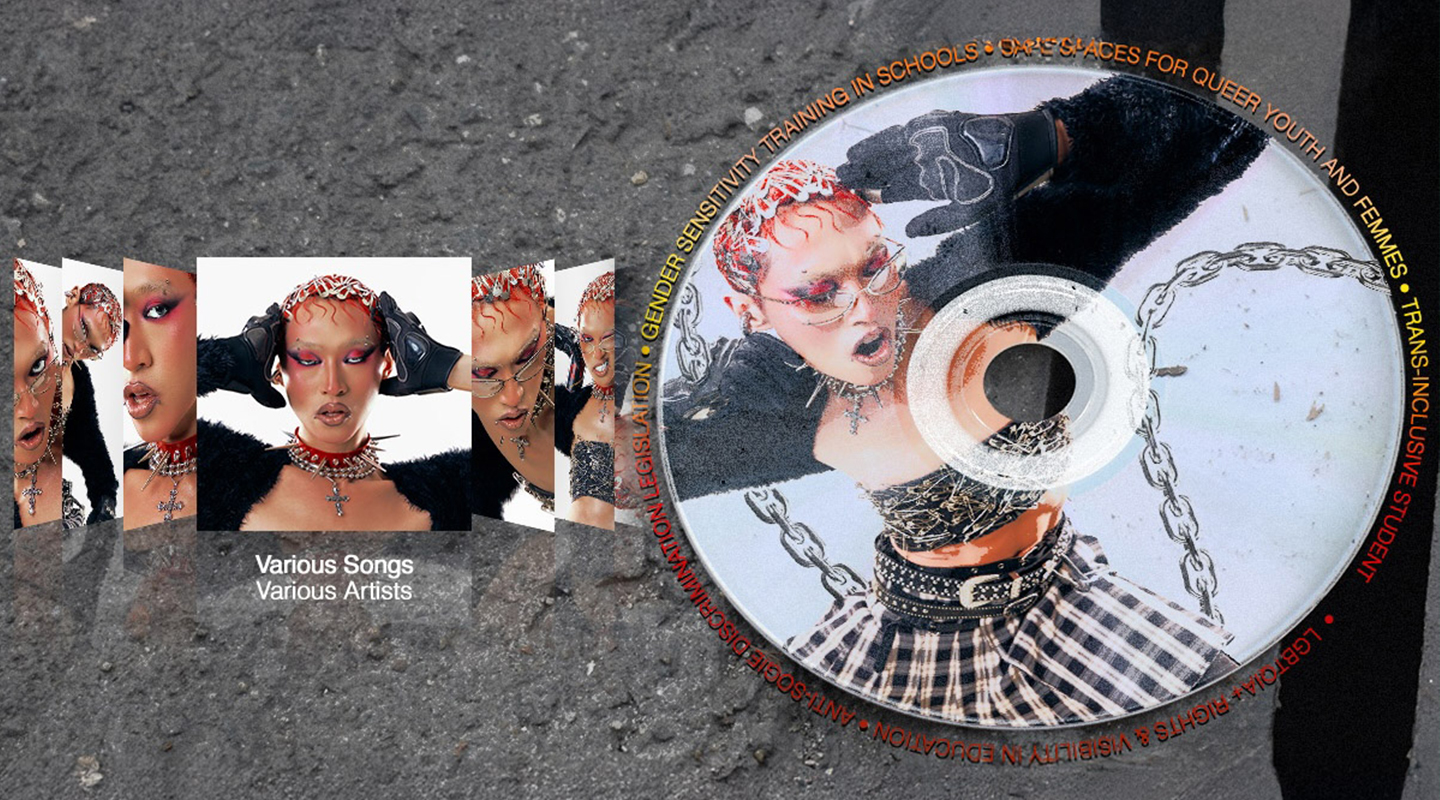

Sadly, the fracturing within the queer community distracts us from the pressing issues we all face. “It’s common knowledge for all of us that there are still a lot of things that need to be done in our country. Some may say ‘Pasalamat, nga kayo di kayo pinapatay. Sa ibang bansa, kapag nalamang bakla ka – wala na,’” says Edgy. “It’s not and will never be a justification of why gratitude should be on our sleeves. Equal rights and laws are yet to be passed. But what’s also sad is how there’s transphobia and homophobia internally, in our own community, which is more heartbreaking, because as far as I know, we should be sharing the same sentiments. The same rights for all of us in the country.”

Many point to the Internet as a means for us to fight for civic equality. Through signal boosting, fundraising, and organizing online — we strengthen the revolutionary toolkit that allows us to resist. But to use the Internet as your only tool has its limitations. “This is very reminiscent of the devastating 2022 presidential elections. We think we’re making progress, but we could be just talking to ourselves,” says Bill. “We could be in an echo chamber. Sometimes the queer community mistakes tolerance for acceptance because of that. No. When the lawmakers succeed in passing bills catered for queers in all forms and shapes, I will say that we as a country are ready to progress into [queer] acceptance.”

Written by Andi Osmeña

Art by Matthew Fetalver